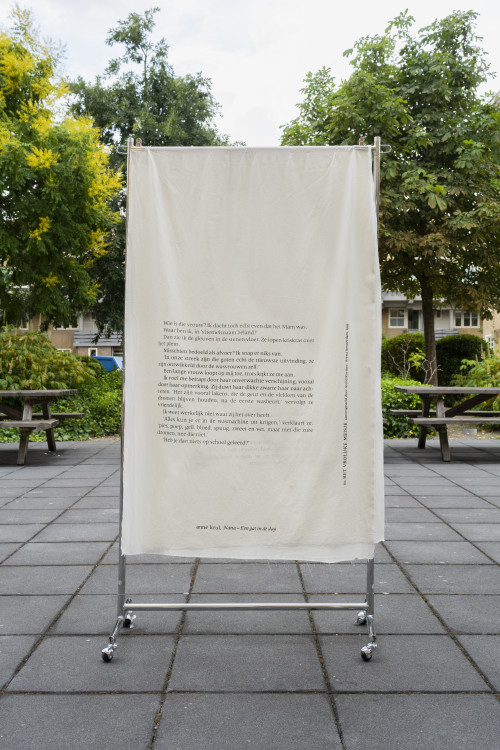

Image: anne krul and Tabea Nixdorff, Wasgoed/ Laundry, 1995/2025, four silkscreens on textile displayed on selected balconies of the Justus van Effencomplex, 90 x 136cm. Text excerpts from the short story ‘Nana – een gat in de dag’, first published in Het vrolijke meisje (ed. Astrid Roemer), Amsterdam, 1995. Silkscreened at Plaatsmaken, Arnhem, with Simon Groot Kormelink.

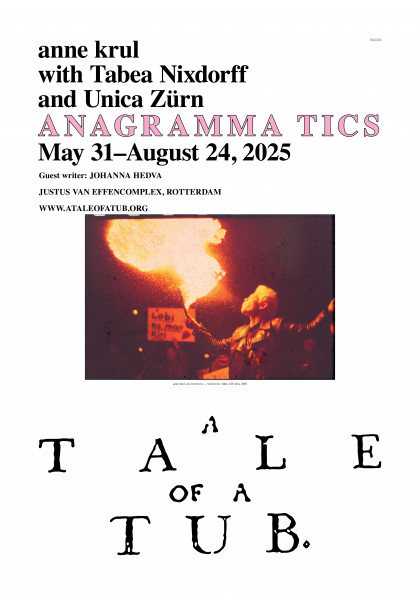

ANAGRAMMA TICS

ANNE KRUL with TABEA NIXDORFF and UNICA ZÜRN

May 31 – August 24, 2025

Guest writer: JOHANNA HEDVA

We first encountered the work of anne krul during a public talk in 2023, within which she projected an image of a truly abstract, colourful painting and stated, dryly yet comedically, ‘This is a depiction of what it is like to work in an institution’. Hooked by the absurdity, laughs followed, as did the immediate feeling that krul had a very embodied understanding of the importance of rendering often illegible experience visible through abstraction.

As a Black visual artist, writer, poet and activist, krul was active throughout the 1990s in various LGBTI+ and women’s organisations, including the International Lesbian Information Service (ILIS), ZAMI—a self-organising initiative for and by black, migrant and refugee women —and Strange Fruit the Real—a queer collective active in the Netherlands from 1989–2002 that supported gay, lesbian, bisexual and trans youth from different cultural backgrounds. With a focus on a non-hierarchical self-help approach, these organisations offered support and conversation without taking the role of experts. Rather, they used creative discourse, activism, art and poetry to effect change. Throughout these many years of organising, and in the spirit of working with art and poetry as a tool for change, krul was also always working away on her solo artistic practice. Spanning painting, video collage, slide installations, sculpture, audio works and anagram poetry, this aspect of krul’s work is widely undercirculated and little known—despite the fact that her political work was so instrumental in ensuring better living conditions for so many young people in the Netherlands.

With this in mind, ANAGRAMMA TICS takes the form of an unconventional retrospective, wherein the various facets and outputs of krul’s practice—anagram poetry, art making, education, organising, collaboration and intergenerational dialogue—will be on show for many to see for the very first time. To make this exhibition, krul has worked with artist and typographer Tabea Nixdorff, a pre-existing collaboration which has seen the pair produce new audio works while also translating krul’s anagram poems—a type of poetry made with the guiding principle that either each line or each verse is written with the same set of letters as all other lines or verses in the poem—into spatial installations and sculptures, building on their overlapping interests in poetry and found language, as well as the restrictions inherent to writing.

Joining krul and Nixdorff is Unica Zürn (1916–1970), an author and artist remembered for her works of anagram poetry and automatic drawing. A key component of the exhibition will be a reading space centred around an anagram poetry archive that krul has been building since the 1990s, within which Zürn acts as both a guiding inspiration and leading figure. To honour Zürn’s influence on krul, to ‘sit alongside each other’, as krul puts it, a collection of her publications and works on paper will be on display, evidencing the dialogical commitment inherent to krul’s practice: if it wasn’t for Zürn, she notes, she wouldn’t be making anagram poems.

Throughout the exhibition, unedited image collections turn into films, the detritus of social poetry gatherings becomes slide projections, hoarded objects are refigured as asemic writing and words and their corresponding letters are literally disorganised on the page, arriving at both new configurations of meaning and a refusal of meaning all together. What results is an expression of experience, both the experience of grappling with language on a personal level— ‘language is a virus’, krul asserts to us—and the instrumentalisation of language on an institutional level, a reference to the social disciplining of so-called ‘deviant’ or ‘abnormal’ behaviour via language throughout history. It is here where krul began writing anagram poems in the first place as, in learning from Zürn, it was a way to live with all her voices. Put frankly, in this exhibition, erroneous and unruly language is a practice of defiance worthy of celebration.

With peer learning as a core value of krul’s practice—each one teach one—an additional feature of the exhibition will be a comprehensive education program, developed in conversation with A Tale of A Tub’s education curator Lisanne Janssen and spanning collaborations with organisations ranging from TENT, Kunstinstituut Melly, Kasteel Spangen and IMC Weekendschool, among others. More details to follow!

Events

Saturday, May 31, 2025, 5:00 – 8:00 PM

Exhibition Opening: ANNE KRUL with TABEA NIXDORFF and UNICA ZÜRN: ANAGRAMMA TICS

Saturday, May 17, 2025, 2:00 – 4:00 PM

Furniture Building Workshop: Part 1

Saturday, May 24, 2025, 2:00 – 4:00 PM

Furniture Building Workshop: Part 2

Saturday, August 23, 2025, 5:00 – 6:00 PM

Literary text production is not my goal: Publication launch and Finissage

Saturday, August 23, 2025, 2:00 – 4:30 PM

Zine-making with anne krul and Tabea Nixdorff

Publications

Bulletin 2/2025

by Johanna Hedva

anne krul with Tabea Nixdorff and Unica Zürn

Limited edition The Clock Wife sweater

Hand-printed by Philipp Gulfer with Nor Akelei

literary text production is not my goal

anne krul

Biographies

ANNE KRUL (1958) is a visual artist, poet, archivist and activist. In the nineties she was active in various LGBTI+ and women’s organisations such as Strange Fruit, the international lesbian organisation ILIS and in ZAMI, an organisation for black, migrant and refugee women. In 2014 she published Anagrammatics - ars combinatoria, her first publication dedicated to anagram poems, visual arts and their interplay. As visual artist, in 2018 krul made the travelling multimedia exhibition Sensitive Bitches – A journey through identities with fellow artist vita s. She also contributed to the exhibitions Diasporic Self – Black Togetherness as Lingua Franca (Framer Framed, 2019), as well as Proud Aliens (2021), Hybrid Garden (2023) and Metamorphosis Manifesting (2024), all part of the artist community Open Atelier at Framer Framed, Amsterdam.

TABEA NIXDORFF (1986) is an artist, typographer and researcher. Her artistic practice involves (self)publishing, writing, sound and language based performances, collaborative learning and social gatherings. Often working with/in archives or libraries, Tabea’s works delve into micro-histories while touching upon broader themes such as omissions and distortions in historical narratives, embodied knowledges, queer belonging and a feminist poetics of error. Her essay Fehler lesen. Korrektur als Textproduktion [Reading Errata. Correction as Textual Production] was published by Spector Books (Leipzig, 2019). In 2023, Tabea founded the publication series Archival Textures in Arnhem, building on extensive research in queer and feminist Dutch archives.

UNICA ZÜRN (1916–1970) was an author and artist. The writings and artwork for which she is best known were mostly produced throughout the 1950s and 60s, during which time she began to experiment with automatic drawing and anagrams. Her surrealist drawings were painstakingly constructed out of finely rendered, repetitive shapes and lines, produced almost exclusively in ink, pencil and gouache and often serving as illustrations for her writing as wel as being exhibited in their own right. Her published texts include Hexentexte [The Witches’ Texts] (1954), a book of anagram poetry accompanied by drawings, and the semi-autobiographical Der Mann im Jasmin [The Man of Jasmine] (1971), which has since acquired a cult following. Parts of the latter text were posthumously published again in the book The House of Illnesses [Das Haus der Krankheiten] (1986), in which Zürn’s drawings and writing co-exist in the artist’s originally conceived way.

JOHANNA HEDVA is a Korean American writer, artist and musician, who was raised in Los Angeles by a family of witches. Hedva’s practice cooks magic, necromancy and divination together with mystical states of fury and ecstasy, and political states of solidarity and disintegration. They are devoted to deviant forms of knowledge and to doom as a liberatory condition. Most recently, Hedva is the author of the essay collection How To Tell When We Will Die: On Pain, Disability, and Doom, published by Hillman Grad Books and Zando, New York. Their latest album, Black Moon Lilith in Pisces in the 4th House, was released on crystalline morphologies and Sming Sming in 2021 and their artwork has been shown at Gropius Bau, Berlin; JOAN, Los Angeles; the Institute for Contemporary Arts and Camden Arts Centre, London; Amant Foundation and Performance Space, New York; and the 14th Shanghai Biennial, among many others.

Support

This exhibition has been made possible thanks to the Mondriaan Fonds, Gemeente Rotterdam Cultuurplan and Jaap Harten Fonds.

Eau De Protection

By JOHANNA HEDVA

You’re catching me at a weird moment. In November last year, I died. In December I took a holiday; in January I fled from fire and smoke in Los Angeles; in February I finally got so tired that I had to lie down because I couldn’t walk anymore; in March I lost my mind; and in April I was slouching towards resurrec- tion, stuck in the birth canal but not yet reborn. The in- vitation to write this text arrived then, when I was still stuffed into the warm dark. The future was veiled. The walls around me were close and cramped. I’d left LA to be in New York City with my partner. Even though New York was freezing and rainy and grey, it seemed better than being alone in Los Angeles. I still could not get out of bed, but when I could sit up, I’d stare out the window of our sublet in Bed Stuy, look into the apartment building across the street. I’d wonder how, exactly how, I was going to bear this? The email came in asking if I could write something about ‘deviant knowledges,’ a phrase from my artist statement about what I am devoted to—at the same moment that I was being tended to by a care group, of friends, family and lovers, tasked with ordering me food, sending money and memes, checking in on me every couple hours. It was not the first time I was dependent on such actions from a group of friends, and it will not be the last. Their job was simple: to keep me alive. Their job was simple—and who among us knows how to do it?

What struck me about this particular moment, in spring 2025, was that everyone in the care group was also in some form of crisis and dependent on collec- tive care to stay alive. There was a friend recovering from cancer surgery and chemotherapy, about to start radiation, and we ordered groceries for each other. There were new parents overwhelmed by anxiety and depression about raising their infant in fascism, and I would sit on their couch in the afternoons while their baby rolled and squealed in their arms, and they told me how dark their mood had gone during winter. A dis- abled friend was in and out of the hospital dealing with a lingering infection, and they kept sending me money even when I told them to stop. One friend, who signed up to order me food on Tuesdays and Thursdays, had just lost everything in the LA fires of January. All the documentation of thirty years of their work as a the- atre maker, all their possessions, furniture, books, the ashes of their ancestors: gone. And still, twice a week, for a month and counting, I woke up to texts from them, saying, “Hello! How are you feeling today? What are you hungry for?” They ordered me soup, salads, coffee, cookies.

Last weekend, in the middle of April, the sun came out in New York City for the first time in a month. I met some disabled friends from the care group in a park. We sat outside for the afternoon. It was hot and bright enough for us to wear sunscreen, to shield our eyes from the sun, to sweat. Upon arriving, I shout- ed, “We’re not dead yet, bitches!” Everyone had their canes and cute outfits. Everyone, at some point in the hang, had to deal with a part of their body malfunc- tioning: pain, bleeding, brain fog. The amount of times the phrase ‘I love you’ was said!

One friend I hadn’t seen since before the COVID pan- demic, and it felt amazing to be together in synchronous time with our bodies. Our relationship is sustained by leaving long voice notes for each other, but today, we were both here, wearing lipstick and jewellery. Our birthdays are close together, two Tauruses, about a week away. We spoke about our lifetimes of physical disability and mental illness, suicidal thoughts, our activism, our sense of doom, and how we haven’t succumbed yet.

I complimented her new perfume. She complimented mine and wanted to know what it was. “It’s called Eau de Protection,” I said. Water of protection.

She inhaled with her eyes closed and smiled. “Ughhhhhh,” she said.

“What is that smell?”

“It’s a weird rose,” I said. “There’s a blood accord list- ed in the ingredients.”

She nodded. “A rose that smells like blood. Perfect.”

“Protect me, water,” I said. “Water: protect us.”

I want to make a grand statement here. I want to say something about the interdependency of survival, about how care can be shared as much as pain, about friends showing up for each other as the world burns, about wearing perfume on days when you don’t know how to keep living. While writing this text, I learned the word ‘recrudescence,’ which means the outbreak of something after a period of rest or inactivity. It can be used to describe a disease, an infection, but it is also used to describe springtime.

I went home to LA in time for May 1. Spring had ex- ploded. My garden was overgrown, weeds crowding out the nasturtiums and rosemary. Hummingbirds, mock- ingbirds and stray cats had taken over my yard while I was gone. They hovered at the edges and watched me. I ordered food for them.

Maybe I don’t need to make a grand statement about how insistent life can be, how we cling to it and it clings to us, how we come back from the dead, recrudescent, and what protections are required for that to happen again and again. Maybe I just need to note that yes, I feel old, that sometimes I don’t know how to bear it, but I’ve not stopped yet. Maybe it’s enough to say that the perfume I bought while stuck in the birth canal— dead, resurrected, reborn—smells like a weird rose sprouting from blood.

Image: anne krul and Tabea Nixdorff, Wasgoed/ Laundry, 1995/2025, four silkscreens on textile displayed on selected balconies of the Justus van Effencomplex, 90 x 136cm. Text excerpts from the short story ‘Nana – een gat in dedag’, first published in Het vrolijke meisje (ed. Astrid Roemer), Amsterdam, 1995.

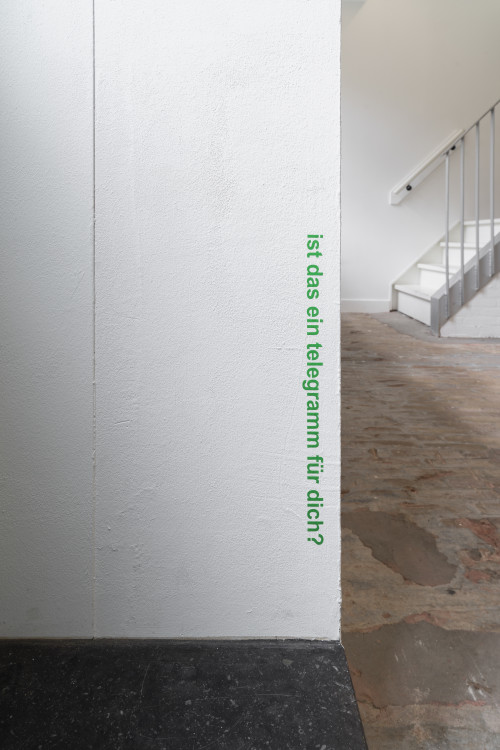

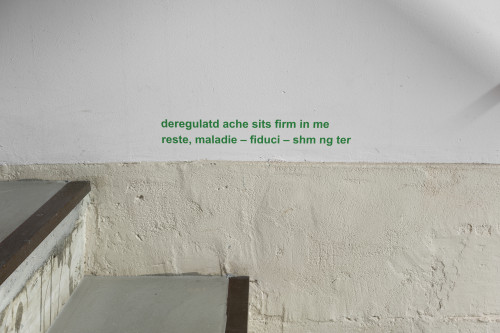

Image: anne krul and Tabea Nixdorff with Unica Zürn, Tele-Anagram, 1960/2024–25, 2025, vinyl text, dimensions variable.

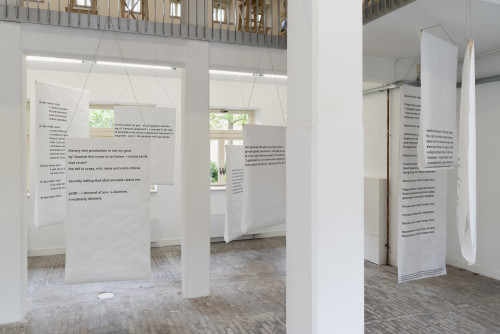

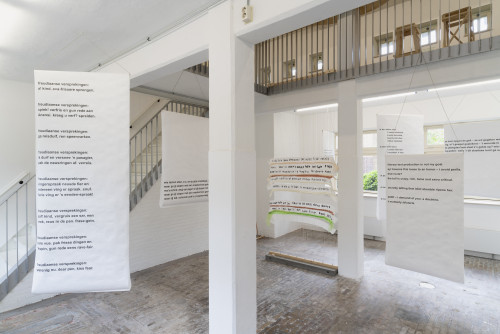

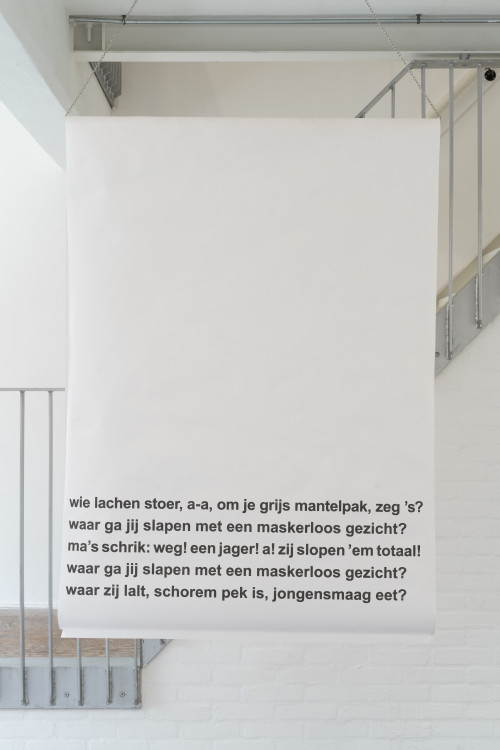

Image: anne krul, anagram poetry, 2014–2025, inkjet prints on Tyvek, metal chain, wood, 13 banners, each 91cm x various lengths. Typography and translations with Tabea Nixdorff.

Image: anne krul, anagram poetry, 2014–2025, inkjet prints on Tyvek, metal chain, wood, 13 banners, each 91cm x various lengths. Typography and translations with Tabea Nixdorff.

Image: Tabea Nixdorff, Weaving Loom, 2025, thread, concrete, wood with collective anagram writing by students of the Stichting IMC Weekendschool, made with anne krul and Tabea Nixdorff, 328 x 146cm. Loom by Ramón Jiménez Cárden.

Image: Unica Zürn, Plan des Hauses der Krankheiten [Plan of the House of Illness], reproduction from the book Unica Zürn: Das Haus der Krankheiten (facsimile of original manuscript from 1958), published by Brinkman & Bose, Berlin, 1988.

Image: anne krul, anagram poetry, 2014–2025, inkjet prints on Tyvek, metal chain, wood, 13 banners, each 91cm x various lengths. Typography and translations with Tabea Nixdorff.

anne krul and Tabea Nixdorff with Unica Zürn, Tele-Anagram, 1960/2024–25, 2025, vinyl text, dimensions variable.

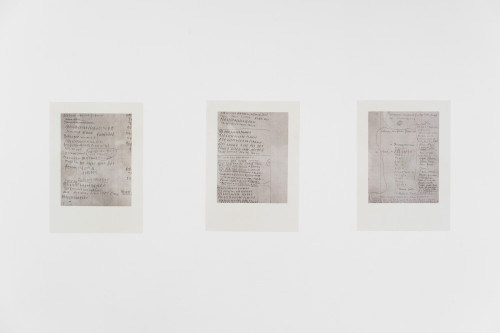

Image: Unica Zürn, Untitled, year unknown, reproduction from Anagramme (Vol. 1, Collected Writings), published by Brinkman & Bose, Berlin, 1988.

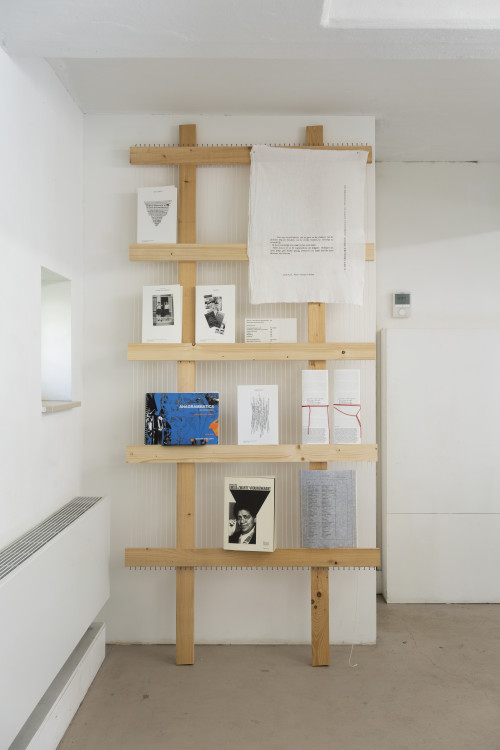

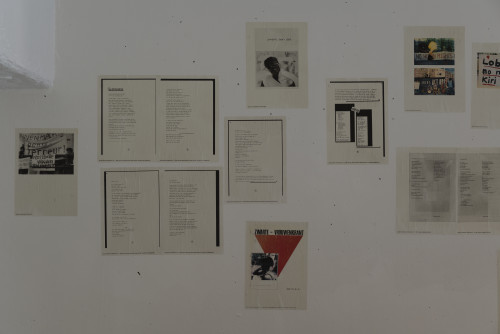

Image: anne krul and Tabea Nixdorff, Reading Bar, 2025, plywood, assorted printed matter, approximately 570 x 310cm. Collection includes reading materials spanning anne krul’s decades-long personal anagram reference library, Tabea Nixdorff’s personal library and additional materials on loan from Atria, Institute on Gender Equality and Women’s History, Amsterdam. Reading bar built by Tomi Hilsee, with bar stools by Liam, Chiara, Rosa, Alexander, Isabelle, Alisa, Max and Alban, made during a children’s workshop accompanying the exhibition.

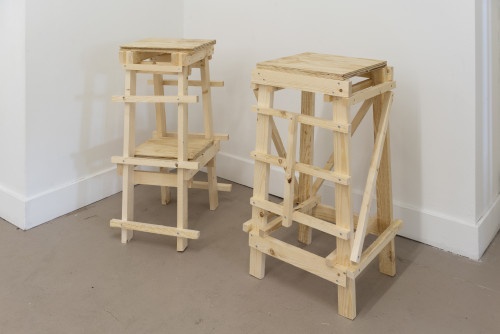

Image: Reading Bar stools by Liam, Chiara, Rosa, Alexander, Isabelle, Alisa, Max and Alban, made during a children’s workshop accompanying the exhibition.

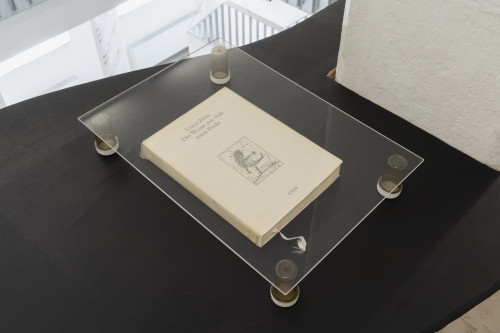

Image: anne krul and Tabea Nixdorff, Reading Bar (detail), 2025, plywood, assorted printed matter, approximately 570 x 310cm.

Image: anne krul and Tabea Nixdorff, Reading Bar (detail), 2025, plywood, assorted printed matter, approximately 570 x 310cm.

Image: anne krul and Tabea Nixdorff with Unica Zürn, Tele-Anagram, 1960/2024–25, 2025, vinyl text, dimensions variable.

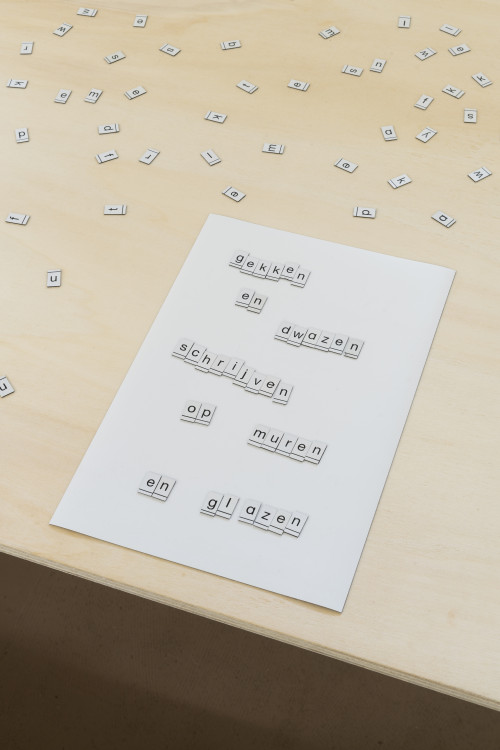

Do-It-Yourself Anagram workshop space, 2025, workshop tables with magnetic letters for arranging anagrams, a scanner and a printer for duplication, dimensions variable.

Do-It-Yourself Anagram workshop space (detail), 2025, workshop tables with magnetic letters for ar- ranging anagrams, a scanner and a printer for duplication, dimensions variable.

Image: Bookstand with publications by anne krul and Tabea Nixdorff available for purchase.

Image: anne krul and Tabea Nixdorff with Unica Zürn, Tele-Anagram, 1960/2024–25, 2025, vinyl text, dimensions variable.

anne krul, Herhaalrecept [Refilled prescription], 2025, collection of medication bottles installed in widow frames, dimensions variable.

Image: Unica Zürn, Ein Märchen Buch für Friedrich Schröder-Sonnenstern [A Storybook for Friedrich Schröder-Sonnenstern], 1963–1964, 17 watercolor and ink drawings on six 6 folded sheets of paper, double page framed, 32 x 25cm; and Unica Zürn, Ein Märchen Buch für Friedrich Schröder-Sonnenstern [A Storybook for Friedrich Schröder-Sonnenstern], 1963–1964, 17 watercolor and ink drawings on six 6 folded sheets of paper, single page framed, 32 x 25cm.

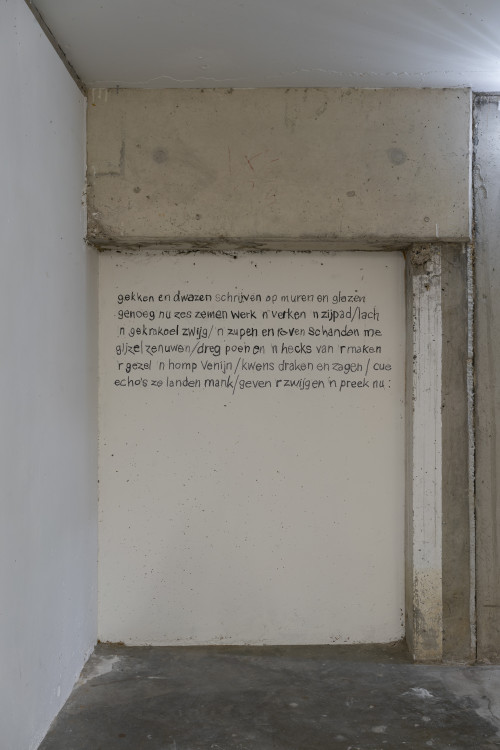

Image: anne krul, gekken en dwazen schrijven op muren en glazen [crazy people and fools write on walls and glasses], handwritten poem on wall, 160 x 130cm.

Image: anne krul, Asemic Writing, 2025, installation of found objects, gathered by anne krul between 2000–2025, 200 x 350cm.

Image: anne krul, Asemic Writing, 2025, installationof found objects, gathered by anne krul between 2000–2025, 200 x 350cm

Image: Unica Zürn, Anagramm aus der Zeile [Anagram from the Line], 1967, signed, dated and inscribed on recto ink on board, 31.1 x 26cm; and Unica Zürn, Untitled, 1960, double-sided sheet from Orakel und Spektakel [Oracle and Spectacle], Book V (unpublished manuscript), ink, India ink and collage on paper,

32.9 x 25.2cm.

Image: anne krul, Drieluik [triptych], 2025, installation of three Dia slide sequences, from left to right: Deconstructie-constructie, 2010, 4min 20sec;

Een Vlieger Slaat De Mislukte Dochter I [A Kite Slaps The Failed Daughter I], 2015, 4 min 9 sec; Vlieger Slaat De Mislukte Dochter II [A Pilot Slaps The Failed Daughter II], 2015, 4 min 46 sec.

Image: Group Zwarte Vrouwen Nijmegen/PulpTV, Zwart aan Zet, 1985, VHS video installation with poetry reading by anne krul and others, 5 min 40 sec. Features excerpts from the book Zwart aan Zet, filmed on November 2, 1985, by PulpTV at feminist bookshop De Feeks and during the book launch on November 8, 1985, at Villa Lila Nijmegen. Source: Lesbisch Archief Nijmegen.

Image: anne krul, Poets in the Kitchen, 1994, digitalised Dia slides of photographs inspired by feminist and queer poetry gatherings created in honour of ZAMI’s birthday in 1994, custom table, assorted archival objects, assorted archival printed matter, dimensions variable.

Image: anne krul, Poets in the Kitchen (detail), 1994, digitalised Dia slides of photographs inspired by feminist and queer poetry gatherings created in honour of ZAMI’s birthday in 1994, custom table, assorted archival objects, assorted archival printed matter, dimensions variable.

Image: anne krul, Poets in the Kitchen (detail), 1994, digitalised Dia slides of photographs inspired by feminist and queer poetry gatherings created in honour of ZAMI’s birthday in 1994, custom table, assorted archival objects, assorted archival printed matter, dimensions variable.

Image: anne krul and Tabea Nixdorff, Will I Meet You Sometime?, 2025, audio piece, endless loop; Tabea Nixdorff and Nicha Keeratiphanthawong, Meditation Sleeves, 2019, fabric, polycotton filling, various sizes; and Tabea Nixdorff, Errata, 2025, video projection, endless loop.

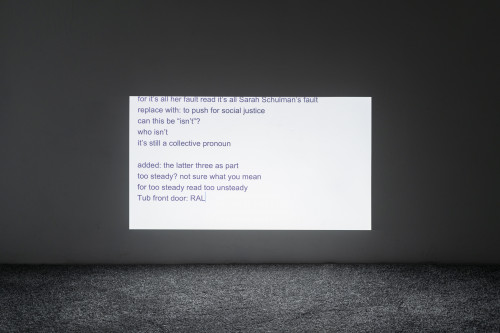

Image: Tabea Nixdorff, Errata, 2025, video projection, endless loop.